Disclaimer: This post may contain Amazon affiliate links. Sudachi earns a small percentage from qualifying purchases at no extra cost to you. See disclaimer for more info.

Hidefumi Aoki

Contributing Writer

Hidefumi started his career at Hotel Metropolitan “HANAMUSASHI” in 1989, and since then he has worked as a chef and a head chef at various restaurants and ryokan all across Japan for more than 30 years. He holds a chef’s license and a fugu chef’s license in Tokyo.

Featured Comment:

“This was amazing. I’ve often stood in the aisle of HMart in the US and wondered which kombu I should buy. This demystified it for me. Many other Japanese websites don’t differentiate about ingredients to the extent that you do. Many thanks for that.”

– KAT

What is Kombu Kelp?

Kombu is an intriguing variety of seaweed that originates from the cold, deep recesses of the ocean. This unique marine vegetable is available in both its natural state, as shaped by the whims of nature, and in cultivated forms, as developed through agricultural practices.

It’s worth noting that Hokkaido, a region in Northern Japan, is responsible for a substantial 95% of the country’s kombu yield. To maintain the highest standards, Japan employs a meticulous grading system ranging from 1 to 6 to categorize the quality of the harvested kelp.

The grading process is based on a multitude of carefully considered factors. These encompass not only the time of harvest and the specific location of the collection but also a comprehensive list of physical attributes. The weight, length, width, thickness, shape, and color of each kombu specimen are all assessed prior to its distribution.

Kombu that has been damaged or bears imperfections is not disregarded but is classified and shipped separately as substandard. Thus, every harvested piece of kombu, irrespective of its quality, finds its place in the realm of gastronomy. This, indeed, underscores the inclusive journey of kombu from the cold sea to the warm hearths of our kitchens.

The Origin

Dating back to the Jomon period (around 1400 BCE – 10th century BCE), the culinary use of kombu (昆布), or kelp, has a storied past. Its influence grew substantially during the Edo period (1603-1867) when it became a significant trading commodity. Merchants transported kombu from Hokkaido to various regions, including Kyoto, Osaka, Edo (now Tokyo), Kagoshima, Nagasaki, and Okinawa, using ships known as Kitamae-bune (北前船). This network came to be known as the “kombu road (昆布ロード)”, leading to unique kelp dishes in each region.

The life cycle of kelp starts with the fall release of spores that grow into small plants in winter. The plants attach to rocks in spring, growing rapidly in nutrient-rich seawater until nutrient depletion halts growth in summer. However, autumn’s cold winds and turbulent waves churn up nutrients, promoting growth again. By the second summer, the kelp is ready to be harvested.

Conversely, farmed kelp is cultivated by wrapping kelp spores around a rope and submerging it in the sea. The two main types are the one-year promotion cultivation, harvested after one year, and the slower-growing two-year cultivation.

The Science of Umami

Kombu, dried bonito flakes, and dried shiitake mushrooms are like the holy trinity of Japanese umami flavors. Each contributes a unique essence – inosinic acid from bonito flakes, guanylic acid from shiitake, and glutamic acid from kombu. It’s this glutamic acid that grants kombu its delightfully subtle and gentle flavor.

Indeed, when it comes to umami-rich foods, kombu is a shining star in the Japanese culinary world. It outshines even other foods renowned for their glutamate content, like cheese and tomatoes. The secret lies in the soluble nature of glutamic acid. This prime umami compound in Japanese seasonings dissolves easily in water, infusing a mouthwatering dashi broth whether you’re simply soaking kelp or boiling it.

Now, one might wonder: does living kelp release its umami into the ocean? Well, it turns out that glutamic acid, a core component of dashi, is also crucial for the kelp’s own growth. In living kelp, the cell walls function as a protective barrier, preventing the glutamic acid within the cells from seeping out. But once the kelp is harvested and dried, these cell walls lose their functionality, allowing the umami-rich glutamic acid to easily dissolve in water. Moreover, the drying process breaks down proteins in the kelp, enhancing the glutamic acid content and thus its umami flavor.

The Role in Traditional Japanese Cuisine

Earlier we uncovered the journey of kombu via the Kitamae Ships, sparking off a cascade of unique local cuisines across Japan and cementing itself in the nation’s food culture. But what role does it play in Japanese cuisine today?

Allow me to introduce kombu dashi broth. Light, yet packed with flavor, this broth has the magical ability to inject umami into any ingredient it touches. The ways to use it are as endless as the waves in the ocean.

Vegetables boiled and bathed in kombu dashi, with a simple sprinkle of salt, allow the natural flavors to sing while enriching their taste. Use it as a soup stock for nabe (hot pot), miso soup, and simmered dishes boosts the flavor to new heights.

But there’s more: Immerse kombu in your everyday soy sauce and voila, you’ve got a soy sauce with a mellower, more nuanced flavor. Add a sprinkle of kelp powder to your salt and you’ve created a mild kelp salt. This pairs exquisitely with dishes like tempura and rice balls.

And then there’s Kombu-jime (昆布〆), a technique where white sashimi is nestled between kombu, producing a sashimi bursting with a rich, indulgent flavor.

Dashi broth is the very heart of Japanese cuisine. And kombu dashi, alongside bonito dashi, plays a pivotal role in it. The beauty of kombu is its ability to enhance umami while maintaining the integrity of the original flavors of the dish. It’s almost fail-safe, enhancing nearly everything it touches. In essence, kombu is an integral thread woven into the fabric of Japanese cuisine and culture.

Different Types of Kombu

While Hokkaido is the primary hub for kombu production, the variety of kombu can be as diverse as the areas around Hokkaido where it is harvested. Here’s a quick trip around the region to meet these different characters:

- Rausu Kombu (羅臼昆布): Considered the crème de la crème for soup stock, Rausu kombu boasts the richest and sweetest taste among all kelps. It’s a favorite in Toyama and Osaka. Purchase on Amazon here (affiliate).

- Rishiri Kombu (利尻昆布): This high-grade dashi broth component has a slightly salty, sharp, dark flavor. It crafts a clear soup stock with a sophisticated taste, making it a staple for dashi in Kyoto cuisine. Purchase on Amazon here (affiliate).

- Ma kombu (真昆布): Another high-grade dashi broth contributor, Ma kombu is known for its pure, sweet flavor and lack of peculiarities. It finds a home in various places, including Hokuriku region, Osaka, and Kyoto.

- Hidaka Kombu (日高昆布): An everyday hero, hidaka kombu is used for soup stock in home cooking and can be included in simmered dishes. It enjoys widespread use in the Nagoya area and the Kanto region. Purchase on Amazon here (affiliate).

- Naga kombu (長昆布): This kombu doesn’t get involved in soup stock, but it stars in simmered dishes and salted kelp (shio kombu). It’s mostly savored in Kyushu and Okinawa.

- Atsuba kombu (厚葉昆布): Found in the same areas as naga kombu, this variety has thick leaves and is used for dishes like kombu maki, kombu tsukudani, and vinegared kombu.

- Hoso kombu (細昆布): Harvested in its first year, this kombu is distinctively thin and sticky. It’s typically used for tororo kombu, natto kombu, and kizami kombu.

- Kagome kombu (かごめ昆布): This kombu comes with a pattern on its surface that resembles a basket mesh. It’s very sticky and contains a large amount of tororo content, making it a good fit for tororo kombu, oboro kombu, and Matsumae pickles.

Each variety adds its unique charm and flavor to Japanese cuisine, bringing a symphony of tastes from the seas of Hokkaido to our plates.

How to Make Kombu Dashi

From here, I, a professional Japanese chef for more than 30 years, will show you how to make dashi from kombu (kelp).

How to choose

While various types of kelp can be used for culinary purposes, Rausu kombu, Rishiri kombu, Ma kombu, and Hidaka kombu are renowned for producing superior kombu dashi, a fundamental element of Japanese cuisine.

Hidaka kombu tends to be favored for home use due to its affordability. In contrast, professional chefs might choose between Rausu kombu, Rishiri kombu, or Ma kombu, depending on the specific culinary requirements and personal preferences.

Two different methods

There are two primary methods to prepare kombu dashi: Mizu-dashi (soaking in water) and Ni-dashi (boiling in water). The chosen method often correlates with the kombu’s thickness.

Mizu-dashi refers to cold water extraction, whereby the kelp is simply soaked in water to achieve a clean and elegant taste. This method is particularly effective with Rausu kombu and Ma kombu due to their propensity to yield excellent stock.

On the other hand, Rishiri kombu’s harder and firmer structure makes it less suitable for mizu-dashi extraction, as the desired flavors can be harder to draw out.

Ni-dashi involves boiling the kelp, allowing the rich, full flavors to be extracted. This method is often chosen when dealing with thicker, firmer kelp varieties.

The Importance of Using Soft Water

The simplicity of kombu dashi lies in its ingredients, which comprise solely water and kombu. However, the water’s quality is crucial. Hard water tends to cause proteins and umami ingredients to form scum, while its calcium content can adhere to the kelp, hindering proper extraction. Japan’s naturally soft water is ideal, but for regions with hard water, a hardness level of up to 30 is recommended.

In terms of preparing the kombu, it’s best to lightly wipe it with a clean, damp cloth. One key point to note is not to wipe off the white powder (mannitol) present on the kelp, it is an essential flavor component and should not be removed.

How to Rehydrate

As mentioned above, preparing kombu dashi, a flavorful kelp soup stock, involves two primary methods: Mizu-dashi (cold water extraction) and Ni-dashi (boiling in water).

For Mizu-dashi, begin with 1 liter of water and 10-15g of Kombu. The process is quite straightforward, simply soak the Kombu in water for a minimum of 3 hours. Once soaked, you can transfer the mixture into a container like a water bottle, and store it in the refrigerator. This prepared stock will maintain its freshness for approximately five days.

On the other hand, Ni-dashi involves a slightly different process. Similar to mizu-dashi, start with 1 liter of water and 10-15g of Kombu. Initially, let the Kombu soak in a pot filled with water for at least 30 minutes. This soaking/rehydrating process aids in better flavor extraction from the Kombu. Following this, gently heat the mixture over low to medium heat until it attains a temperature of 60°C (140°F). Retaining this temperature for roughly an hour allows for the full extraction of the kombu flavor. After an hour, remove the Kombu and switch off the heat source.

A couple of key points to bear in mind when preparing kombu dashi are: firstly, the process of simmering should be slow and steady, and secondly, avoid bringing the solution to a boil. The boiling process could lead to bad sliminess and bitterness, thereby diminishing the overall flavor of the stock.

Kombu Substitute Ideas

When it’s not possible to use kombu, there are several substitutes that can be used to provide a similar umami flavor:

- Concentrated kombu extract: As the name suggests, this is a concentrated extract made from kombu. To make a kelp-like broth, all you need to do is dissolve it in water.

- Powdered kelp: Kelp powder is another great substitute, especially as it encompasses the entire nutritional profile of kelp. Available on Amazon (affiliate).

- Kombucha: This is another option. It uses kelp, sugar, salt, and amino acids as raw materials and is a good seasoning when you want to bring out a kelp-like flavor.

- Ajinomoto: While it’s primarily made from sugarcane, it contains a lot of glutamic acids, the same umami component found in kelp. Available on Amazon (affiliate)

- Tomatoes: This might come as a surprise, but ripe tomatoes are high in glutamic acid, providing a similar umami component to that of kelp. However, keep in mind that tomatoes also have acidity, so be careful what you use them for.

Remember that while these alternatives may provide a similar taste, the results still be different from using real kombu.

I hope this article answered any questions you have about Japanese kombu. If there’s anything else you’d like to know, please comment below!

FAQ

While both kelp and wakame are classified as seaweed, they have distinct characteristics and uses due to their taxonomic differences and environmental adaptability. Kombu thrives only in cold seas and is identified by its thick, singular strip form. While it is indeed edible, its main use is for making soup stock, given its rich umami flavor. Unlike kombu, wakame can grow in warmer seas. It has a thin, leafy structure, spreading out more compared to kelp. Wakame doesn’t yield soup stock, so its primary usage is as a food ingredient in various dishes, often featured in salads, soups, and stews.

There is a difference. Nori is dried seaweed called amanori, which clings to rocks in the sea.

Absolutely! Kombu used for making dashi broth still retains valuable nutrients after the brewing process.

Because of its low umami content, it cannot be substituted for kombu as a dashi broth.

Unfortunately, no other seaweed can produce the same kind of broth as kombu.

No, wakame cannot be used as a substitute for kombu because its umami component is less than that of kombu and the umami component cannot be extracted into water. Each has a different texture when eaten, so it is difficult to use as a substitute for kombu in any usage.

Kombu Dashi (2 Ways to Make Kelp Soup Stock)

Ingredients

Mizu Dashi (cold water dashi)

- 10-15 g dried kelp (kombu) use Rausu or Ma-Kombu

- 1 liter cold water

Ni Dashi (hot water dashi)

- 10-15 g dried kelp (kombu) any kind of kombu, I recommend Rishiri or Hidaka

- 1 liter water

My recommended brands of ingredients and seasonings can be found in my Japanese pantry guide.

Instructions

Mizu Dashi (cold water dashi)

- Rub 10-15 g dried kelp (kombu) with a slightly damp (almost dry) cloth to remove any sand or dirt. Be careful not to rub off any of the white powder.

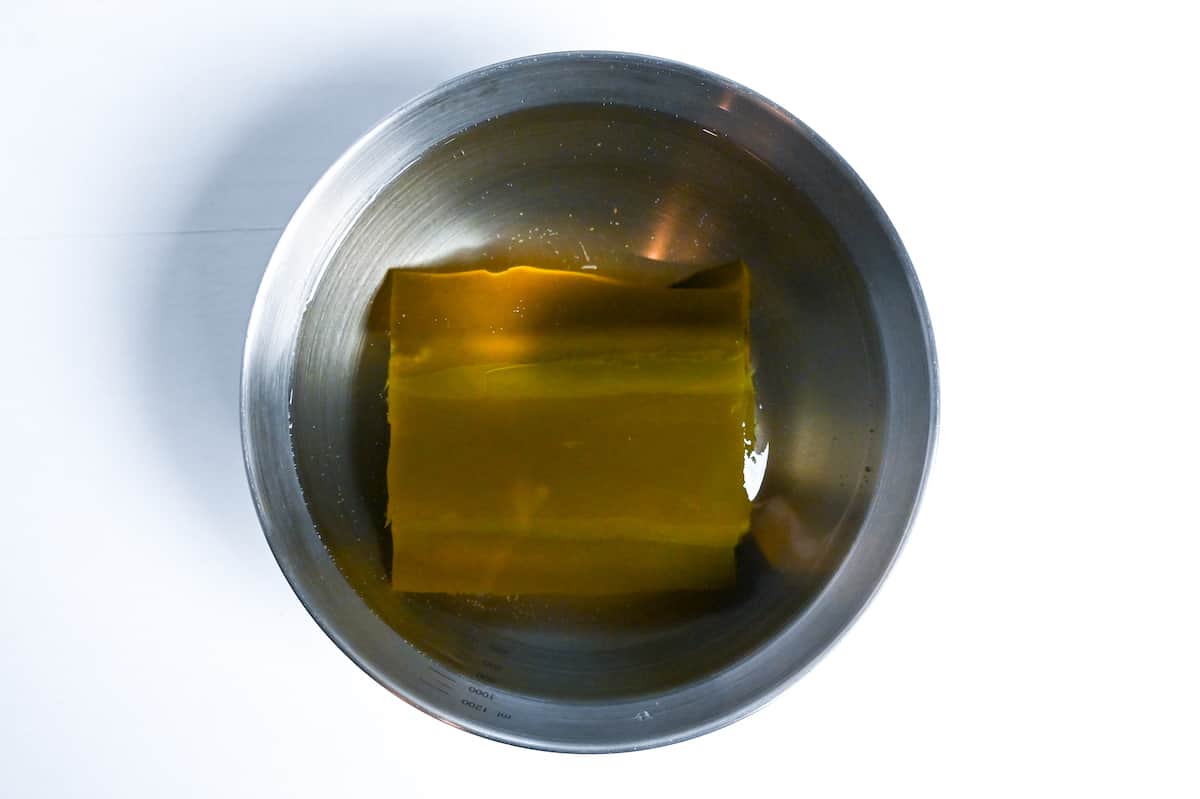

- Place it in a bowl with 1 liter cold water. Cover and allow to soak at room temperature for 3 hours.

- Transfer to a sealable container or bottle and store in the refrigerator.

- Use within 5 days.

Ni Dashi (hot water dashi)

- Rub 10-15 g dried kelp (kombu) with a slightly damp (almost dry) cloth to remove any sand or dirt. Be careful not to rub off any of the white powder.

- Place it in a pot with 1 liter water. Cover and soak for 30 minutes to rehydrate.

- Transfer the pot to the stove and gently heat the mixture over low/medium-low. For full extraction, retain a temperature of 60 °C (140 °F) for one hour. (Be careful not to let it boil)

- Allow to cool before transferring to a sealable container.

- Use within 5 days.

This was amazing. I’ve often stood in the aisle of HMart in the US and wondered which kombu I should buy. This demystified it for me. I have a Japanese store near me and I’m sending my husband to shop for a few items for recipes from your website. Many other Japanese websites don’t differentiate about ingredients to the extent that you do. Many thanks for that.

Hi Kat,

Thank you for your positive feedback! I’m so happy that the article was helpful!

Looking forward to hearing how these recipes turn out 🙂

Yuto